There is a cloud of darkness that shrouds the Bad News Bears, one which causes it to transcend the feel-good kid-movie genre it totally upended in 1976 and that has allowed it to dwell in memory for forty years. Joining the Bears for a few innings so many years later has only allowed me to love them more.

These losers are not lovable, and arguably not even interesting. We applaud their wins because theirs are victories over bullshit sports, bullshit sports cinema, and the bullshit deck, forever stacked against losers.

Indeed, the Bad News Bears couldn’t be made again (though it has been tried!) because it defies every sports narrative we have. Spitting in the face of all sportsmanship, director Michael Ritchie undermines the other, more-typical hard-work stories, repeatedly drawn from the shelf of cinema cliché. The Bad News Bears don’t win, after all; heck, they don’t even always play fair. They simply refuse to be handed second place in a world of wealthy, white elites, who have fixed the game from the start.

For those in need of a synopsis, the plot is simple. An elite southern Californian Little League is forced to add an additional team to mollify a local politician whose son wants to play. This new team, The Bears, are provided a new coach, Morris Buttermaker (Walter Matthau), a sloppy, drunken retired minor-leaguer who cleans pools for living, has no apparent ambition, and has clearly accepted the job for its meagre paycheck.

Figure 1: Walter Matthau’s Morris Buttermaker is played unflinchingly. We’re not supposed to like him, but he does the right thing in the end after all.

Matthau etches his name into legend as Buttermaker, in a performance rivaling any of his other iconic roles, from Willie Gingrich in The Fortune Cookie (1966) to Oscar Madison in The Odd Couple (1968). Buttermaker is a living disaster, albeit a profoundly real one, and is deeply limited in his abilities. He takes the position for cash but begins to knock the left-overs under his care into shape, though they continue to flounder.

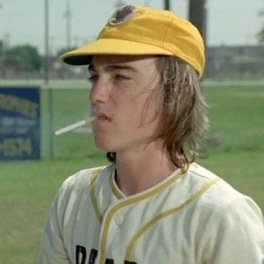

Only by adding a couple of ringers does Buttermaker make his team competitive. These include Amanda Whurlizer (a terrific Tatum O’Neal), the daughter of an ex-girlfriend, as Pitcher, and Kelly Leak (Jackie Earle Haley), a local delinquent, as his power hitter in outfield.

Figure 2: Kelly Leak (Jackie Earl Haley) was my hero.

With this extra talent and a little discipline, the team overcomes its demons and achieves more-than-mediocrity, eventually finding its way to the championship against the arrogant rival Yankees. The Bears lose the game, largely owing to Buttermaker’s insistence that this is a game, and one for kids, rather than an exercise in middle-age masculine self-aggrandizement, embodied by the Yankees coach Roy Turner (a pitch-perfect Vic Morrow).

And so, in the championship game, all players take the plate. The Bears lose, but then gloriously throw the second-place trophy across the mound at their condescending rivals, declaring: “Hey Yankees… you can take your apology and your trophy and shove ’em straight up your ass!”

That’s movie history.

Can We Love Unlovable Losers?

In terms of a plot, that surely doesn’t sound like much. And it might not have been, had not director Michael Ritchie decided to make this sorry script a realist analysis of bourgeois practice and a dark meditation on the inevitable misery of childhood.

Buttermaker is introduced to a makeshift team of pre-adolescent losers, including several clichéd characters, like the brain Ogilvy (Alfred Lutter III) and the fat kid Engelberg (Gary Lee Cavagnaro). But here too is the defiant black kid, Ahmad Abdul Rahim (Erin Blunt), who wants to be Hank Aaron, though couldn’t play his way out of a wet paper bag, as well as two small Latino boys Jose and Miguel Agilar (Jaime Escobedo and George Gonzales), who speak no English, and whose tiny strike zone becomes a matter of tactical advantage. And chief among all these, is Lupus (Quinn Smith), the snot-nosed shrimp who has been bullied into submission.

These kids will never excel at baseball, but their will-to-play becomes fearless, Nietzschian, real.

![]()

Figure 3: Tatum O’Neal and Walter Matthau don’t have much chemistry in The Bad News Bears, and that works just fine.

Simultaneously, Buttermaker meets the elite parent community that governs, coaches, and dictates the terms of the league he is entering, monsters of indescribable elitism and racism, all calmly played to bourgeois perfection. Chief among these is Vic Morrow’s Turner, who coaches the rival Yankees. This patriarch dominates his team and the rest of the little league in a way that is not simply dismissive but also imbued with an arrogance and paranoid defensiveness that goes straight to the shaky masculinity of failing 1970s fatherhood.

Figure 4: Vic Morrow is mean, competitive and monstrous as Roy Turner. I knew coach after coach just like him.

Turner is so insecure of his power that he beats his own son Joey (played in a great brief turn by Brandon Cruz) on the pitcher’s mound, during the climatic championship game, in a sequence that is visceral and unforgettable. This scene lingers like the heat on your face after a violent slap. The world of grownups is one of horror. No child can come away from this film thinking otherwise.

A Bold Spit in the Face

And so, the power of Bad News Bears doesn’t come from its association with derivative films like itself: kid movies about overcoming the odds. More than a few of those had been made by the time Bears hit the screens in 1976. More would follow: feel-good stories about the underdog David overcoming the giant. Those are the kind of thin gruel that Bad News Bears calls out.

Instead, the movie is fueled by elegant and reflective cynicism. Buttermaker drinks his way through every scene, the booze fueling his capacity rather than diminishing it. The kids have little collective morale or joint vision, even as they begin to win, precisely because they are kids: snot-nosed, confused, pre-adolescents. They are not heroes; they’re just mistreated people.

The kids do know one thing. The deck is stacked. And here’s where the movie takes flight.

Figure 5: The team is sloppy, broken, and somewhat lazy. They also know they are up against a machine.

When the team’s ranks are swelled by a girl pitcher and a motor-bike riding trouble-maker, they know they’ve hit bottom. The team’s obnoxious soul, Tanner Boyle (Chris Barnes), boldly yells of the team’s reputation: “Jews, spics, niggers, and now a girl?”. Tatum O’Neils’ Amanda replies, simply: “Grab a bat, punk!” Victory is basically assured after that.

This was Michael Ritchie’s most profound achievement (although I’ve always sorta liked his Fletch 1985). He captured the puniness of the adult world and the long masculine shadow it casts over the lives of young people. He vindicates his losers without a Disney ending or heart-warming moment. The film has neither.

It does have a darkness, however, a richly, lovingly, and cynically crafted mood, which pervades the Bad News Bears and makes it special, and so congruent with how many of us remember childhood. It also allows us a model for how to carry on in an era when arrogant monsters seem to hold the world in their grasp. It tells us:

“Grab a bat, punk!”

Chances that Alexander will like this feature; Good/Fair